Union Street Shops

- Subject:

- Retail

- Project Number:

- 0318

- Date:

- 1965

- Client:

- William and Dickie Quayle, William and Maggie Lacey, Harry and Mildred Golsum

- Location:

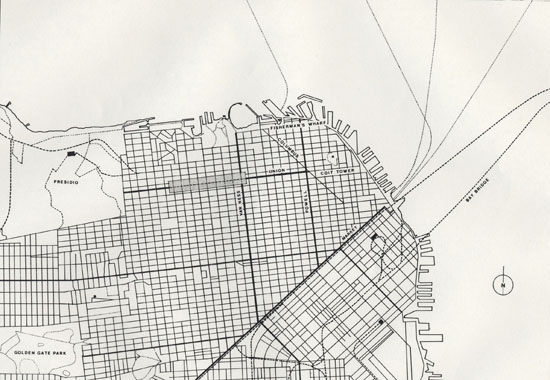

- 1980 Union Street, San Francisco, California

- Project Name:

- Union Street Shops

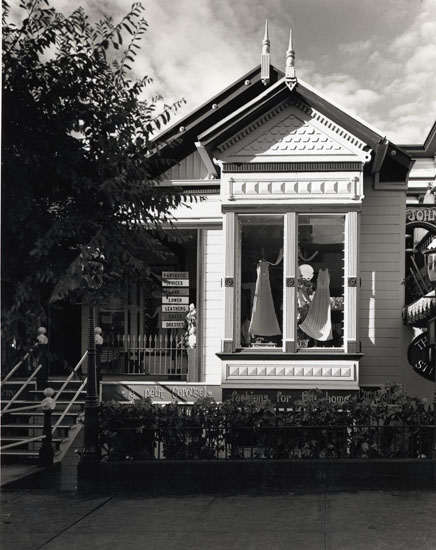

San Francisco’s first settlement was located at the southern entrance to San Francisco Bay, known as the Presidio. Union Street today follows the unpaved road that once linked the Presidio with the city, as buildings extended over time along the shores of the bay to downtown, a mile and a half away. As San Francisco rapidly expanded during the 1849 Gold Rush, the area prospered and become fashionable. Prominent San Franciscans settled here and erected impressive mansions in the 1860s and 1870s, many built in an ornate Victorian style. It was around 1870 when lumber baron James Cudworth built identical Victorian Twin Wedding houses for his daughters at 1980 Union Street.

In 1963, a group of investors––William and Dickie Quayle, William and Maggie Lacey, and Harry and Mildred Golsum––commissioned Beverly Willis to design a new, multi-story building on the site occupied by Cudworth’s now-crumbling, abandoned Victorian buildings, along with a two-story townhouse of the same period next door. The new owners envisioned developing a high-end shopping area that would cater directly to the affluent residents of the adjacent neighborhood, perched high up on the Pacific Heights.

In 1963, the blocks on Union Street between Fillmore and Gough, north of Pacific Heights and just south of the Fillmore Street commercial district, were run-down. The area was being redeveloped by commercial developers, who had begun renovating existing properties into unimaginative, low-budget, three-story walk-ups and flipping them to prospective investors.

Initially the investors who purchased the 1980 Union Street property considered razing the three Victorian buildings. But once the city’s recently adopted commercial parking law requirements were factored into the financial plan, it became clear that building a new structure would result in the loss of too much revenue-generating retail space, in light of the space that would need to be allotted to parking. The other alternative––a renovation of the three original homes––would also fail to provide the investors with enough commercial space to make the project financially viable.

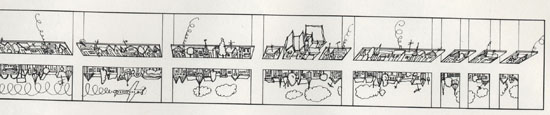

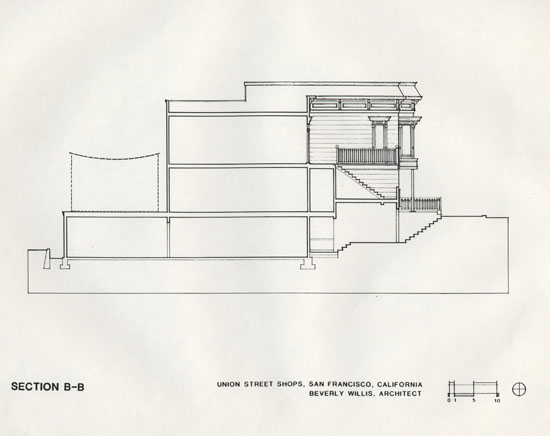

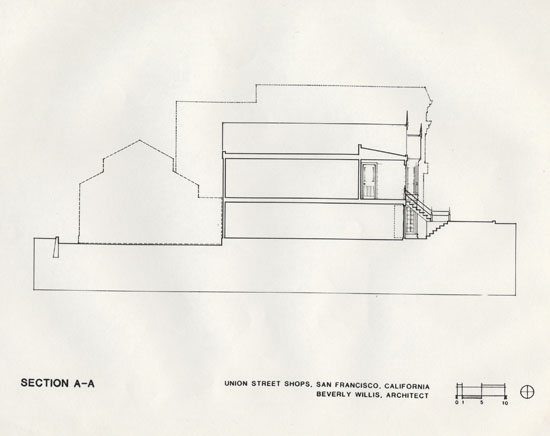

Willis had a brilliant idea. Upon inspecting the foundations, she discovered that due to their poor condition they required replacement. She then offered an innovative solution: she suggested that, because the original structural shell would have to be elevated in order to facilitate new foundation work, they might use this as an opportunity to install an additional story to the building. What appeared a doomed business proposition was brilliantly converted into a vibrant business opportunity. Willis’s solution nearly doubled the complex’s commercial space. It also provided the opportunity to preserve the building’s Victorian facades.

This unusual concept of adapting and re-using antique buildings for contemporary purposes drew national attention. Consisting of nine retail stores and two restaurants, 1980 Union Street Shops became a modern prototype for the adaptive reuse movement of the post–World War II era, in which architects began to “convert crumbling structures of the past into attractive, functional sites to serve modern business needs.” The decision to rehabilitate, rather than raze, the Victorian structures was prophetic of future revitalization efforts in San Francisco. As noted by historian Clare Lorenz, the project “set the style for regeneration of the Union Street commercial district” and “foreshadowed national efforts to restore old buildings in city centers.” In recognition, Willis received the State of California Governor’s Design Award of Exceptional Distinction and an AIA Award of Merit.

Willis’s approach contrasted markedly with the contemporary local practice of demolishing existing buildings in favor of “glass and steel structures, mounting ever higher on San Francisco’s skyline.” Indeed, the bulldozer created many architectural causalities in the 1960s, including New York City’s Pennsylvania Station, demolished in 1963. Along with the Ghirardelli Square and Cannery shopping centers, Willis’s design stands among the nation’s initial explorations of adaptive reuse as a means of revitalization through historic preservation––a concept that had not yet reached other major urban centers in the United States at the time. As William Marlin observed in The Architectural Forum, “the cluster of shops at 1980, done by architect Beverly Willis, inspired community interest in the possibilities of adaptive reuse, making Union Street a linear Ghirardelli Square.” Revitalization projects in San Francisco set a precedent for future national adaptive reuse, including most famously Boston’s Faneuil Hall Marketplace, completed more than ten years after Willis’s Union Street Shops.

Willis replaced the crumbling foundations of the three buildings with a full floor structure. She restored the existing building facades in the Victorian tradition and added a new Victorian-style facade to the new floor below. She designed a porch-like open hallway to connect all three buildings in front. Decks for outdoor dining were added to the front of the townhouse and the rear of the cluster. In front of the twin wedding houses, she installed an ornamental black iron railing with stairs, leading to both the ground floor and second-floor level.

The structures were painted in multiple colors––a background color, together with two colors similar to those popular on period Victorian facades. The Victorian architectural vocabulary resonated with Willis’s childhood memories of her grandfather’s purchase of the Queen Anne–style house that was introduced to the United States at the 1904 World Fair in St. Louis.

National attention focused on the 1980 Union Street project motivated General Motors to feature it in its advertising, photographing the 1964 Chevy Nova in front of the shops.

The project’s success inspired other investors to buy and restore other buildings nearby, resulting in the formation of a commercial district along a five-block stretch of Union Street that would thoroughly transform the deteriorated, low-value area. The group of stores and restaurants became a landmark destination in the region. Decades after its completion, in 1984, the San Francisco Business Times described Willis’s design as “charting the course and the ambience of the well-known shopping and dining mecca we know today.”

This commercial revitalization of one of San Francisco’s oldest neighborhoods encouraged other neighborhood revitalizations. While providing economic benefits to the city as a whole, projects like Willis’s simultaneously preserved the city’s rich architectural character. By rehabilitating three small, derelict properties, Willis’s design for the Union Street Shops ensured the preservation of much of San Francisco’s architectural history and forever altered the city’s economic landscape.

Willis became one of the organizers of the Union Street Merchant Association and served as it first director. In 1966 she opened her own cookware and country furniture store a block away from the Union Street Shops, named the Capricorn.

- Barber, Jean. “Spotlight on Beverly Willis, FAIA.” Women in Architecture October 1988.

- Beebe, Morton, et al., eds. San Francisco. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1985.

- “Success by Her own Rights.” San Francisco Business August 1984.

- “Blueprints By the Bay.” Savvy November 1982.

- Thomas, Lynn. “Restored Commercial Buildings How The City Saves Face.” San Francisco Business October 1973.

- “San Francisco’s Magic Time Machine.” San Francisco Business 8 October 1973: 8-14.

- Marlin, William. “The Streets of Camelot.” The Architectural Forum 1973: 26-38.

- “Union Street Advertisement.” San Francisco 26 July 1970.

- Hayes, Elinor. “Blonde Produces Instant Houses.” Oakland Tribune 24 August 1969.

- “Northern California AIA Design Awards Honor 17 Projects in 1967 Program.” Architecture/West July 1968: 11.

- The Junior League of San Francisco, Inc. Here Today: San Francisco’s Architectural Heritage. Chronicle Books, 1968.

- “Northern Californians Win Top Design Honors.” San Francisco Chronicle 24 December 1966.

- “21 City Scenes.” House Beautiful August 1965: 72-73.

- Examiner Capitol Bureau. “Design Awards To 77.” [No Paper Name], n.d.