Manhattan Village Academy High School

- Subject:

- Government

- Project Number:

- 0807

- Date:

- 1994-1996

- Client:

- New York City Board of Education Facility Division Ramon Cortines

- Location:

- 43 W. 22nd Street, New York, New York

- Project Name:

- Manhattan Village Academy High School

Conceived as an alternative to the traditional high schools run by the New York City Board of Education, Manhattan Village Academy (MVA) was founded in 1993 by MacArthur Foundation Award grantee, the famed educator Deborah Meier. Working closely with leading education reformer Ted Sizer and the Center for Collaborative Education (CCE), she assembled a team to lead the new charter school. Mary Butz joined as school principal, and together Meier and Butz set out to “replace the old, assembly-line model of education with more active and personalized learning.”

As the process evolved, it became clear that what the school founders and educators needed was “a design partner who [would] take the time to create schools according to idiosyncratic specifications” to support innovative approaches to education. On the recommendation of Chancellor Ramon Cortines, in 1995 Butz asked Beverly Willis to design the school.

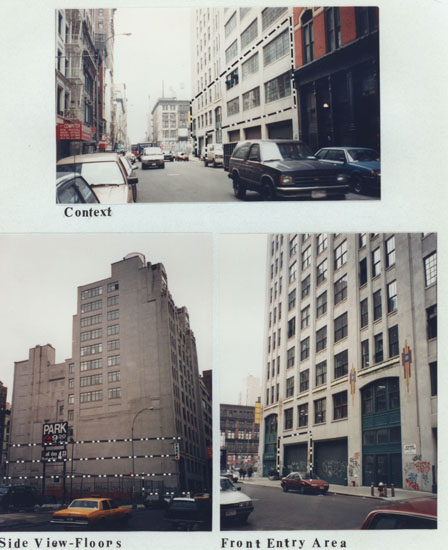

Located on three floors of an existing Beaux-Arts–style office building on West 22nd Street in Chelsea, the design of MVA was a co-venture between the CCE and the Architecture Research Institute, head designer, Beverly Willis. Part of the CCE mission was to advocate for schools that were small enough for all students and teachers to know one another by sight. MVA’s 1996 class had 335 students in grades 9 through 12.

The plan for MVA was to create a revolutionary establishment that would promote design excellence within the country’s largest public education system. Touting the value of good design, Director of Design for the New York City School Construction Authority Kenneth Karpel noted their desire to do “something much greater and more integrated than just aesthetics to take [education] to the next level.” That next level would be achieved through Willis’s design.

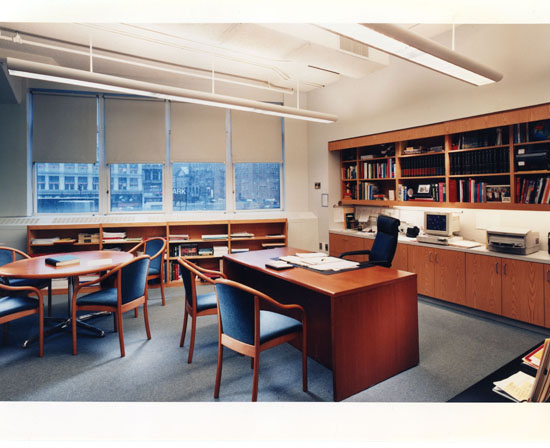

The design intent was to create a customized program that would fit the school’s pedagogy and dignify the very idea of education, thus supporting the administrative, teaching, and learning processes. Meier, a leading national proponent of small school education, saw Willis’s approach to the design of MVA as a remedy for the learning difficulties facing high school students. The New York Times praised the project as possessing “the intimate feel of a private liberal arts high school.”

The American Institute of Architects Committee on Architecture for Education selected for their book the MVA project as one of the national examples of education design excellence.

Not only was it a new idea in education but also a new idea in the architecture design profession. In the first graduating class, every student went on to attend college.

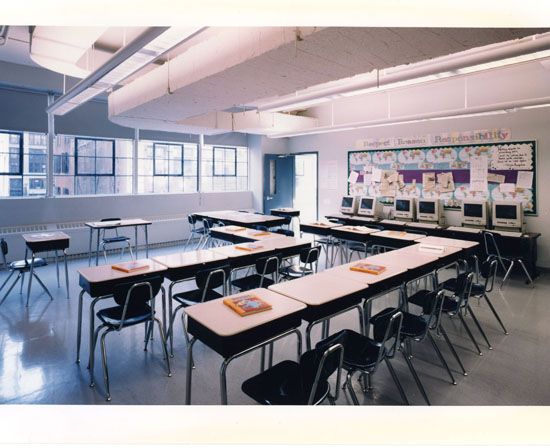

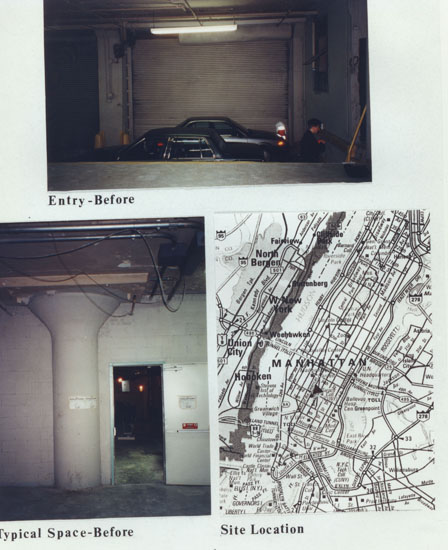

The school is housed within three floors of an existing office building, part of a NYC Board of Education decision to place charter schools in rented spaces. The historic art deco-styled tall building that houses the school is a New York City landmark. The Board of Education’s original proposed plan for the school was what Butz called factory-model blueprints––basic, bland, and thoughtless––that invoked the standard plan of classrooms off a blank, lengthy corridor. In contrast, Willis devised a locus plan− “a cluster of classrooms for each grade around an interior quadrangle space, where teachers have a selection of a variety of spaces to fit a personalized approach to their students’ needs.” The open space at the center of each quad “was known as a ‘cluster,’ or DEAR (Drop Everything and Read) area.”

Writing for Oculus magazine, architecture critic Jayne Merkel states, “at Manhattan Village Academy, the educational philosophy is embedded in the architecture.” Indeed, the philosophy of personalized learning set forth by Butz and Meier was reflected in Willis’ design. In addition to the reconfiguration of the classroom layout, Willis rejected the back-door treatment conveyed by the original plan, which located the entrance in the rear adjacent to the freight exit. Instead, she created a grand high school facade in miniature. Inside its doors, four marble steps ascend to a spiral staircase, leading to the school’s second-floor lobby.

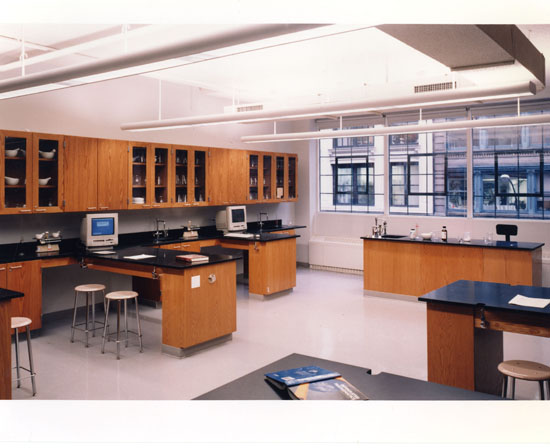

The locus plan consists of clusters of classrooms for each of four grades, all with a common area and joined together by minimal corridor spaces. The locus design open space accommodates 100 students and is encircled by three interconnected classrooms. A science laboratory with a folding wall opens up to one of the classrooms. This arrangement provides teachers with choices for innovative teaching spaces.

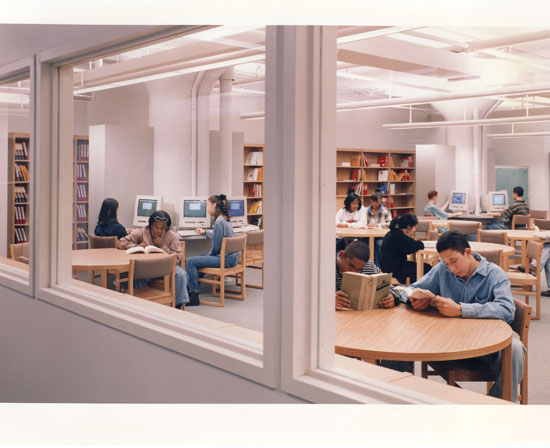

Freshmen and sophomores are clustered together on the second floor, with juniors and seniors on the third. On the second floor, the two clusters are divided by a cafeteria space fenced in by small rails. On the third floor, a dance studio, now used as the music room, separates the two clusters. The third floor also features a multimedia center, complete with a library, study space, another classroom, and computer lab (the school was one of the first in the city to have computers). In addition there is a home economics classroom and an auditorium.

Glass-windowed offices located at the top of the entry stairs allowed teachers to observe students as they came and went. The design also incorporates glass walls and office windows onto corridors and common areas, to allow for continuous monitoring of student activity. In a departure from the hard tile and stone wall surfaces commonly used in schools, Willis used less expensive drywall panels that could be easily maintained by the schools maintenance staff, who kept the school in pristine condition.

Planning and construction were completed within a year of her receiving the commission, in order to meet the Department of Educations’ enormous need for schools to accommodate the waiting lists of students. MVA students came from all parts of New York City. “Through a mix of tenacious advocacy and personal connections,” as one design critic noted, “Willis ultimately became the first outside architect to design and renovate leased space for a New York City public school.”

- AIA Committee on Architecture for Education. Educational Facilities: Exemplary Learning Environments. New York: AIA, 2002. 128-29.

- “Making History.” Oculus November 2000.

- Rogers, Pat. “Renaissance Woman Looking Ahead.” The Southampton Press 13 January 2000.

- Gould, Kira L. “New York City’s Cool Schools.” AIArchitect May 1999.

- Moed, Andrea. “Class Conscious.” Interiors May 1999: 62-63.

- Pierno, Marcus and Sam Tsyrlin. “The Genesis of MVA.” Manhattan Village Academy News April 1996.

- Merkel, Jayne. “Back to School.” Oculus September 1995: 10-13.

- Thrush, Glenn. “One Size Fits None.” Metropolis September 1994: 57.

- “A Case Study: The Loft High School Plan.” ARI Brochure n.d.